The Icelandic tradition of Jólabókaflóðið (literally, Christmas Book Flood) warms my heart, since it involves settling into a comfortable spot,eating chocolate, and reading books. The custom, as I understand it, of giving books (books are, apparently, the default Christmas gift) comes from both Iceland’s long literary history and, more recently, from limited imports of nearly everything but paper during World War II.

Christmas is almost on us, but it’s still not too late to encourage spreading this tradition, and given the state of the world, enjoying Jólabókaflóðið may be the most sensible thing to do in 2020.

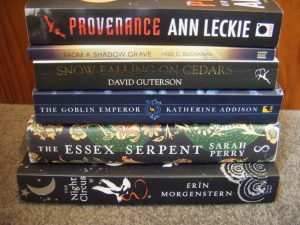

With that in mind, here are the books—some old, some new, some well-known, some obscure—that were most memorable for me this year. In no particular order, they include

- A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine: A superb science fiction novel exploring questions of identity and cultural imperialism, with a likeable, competent, and proactive female protagonist.

- The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison: An enchanting story about the shock power of kindness upending a rigid, Byzantine court when an unwanted, unloved heir ascends to the throne.

- Deltora Quest by Emily Rodda: Middle-grade fantasy filled with good stuff: unusual creatures, challenges requiring cooperation and trust to overcome, heroism and self-sacrifice for the greater good, and puzzles.

- Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson: Highly atmospheric mystery/courtroom drama that’s a deep dive into bigotry against Japanese-Americans during and after World War II.

- The four-part Murderbot Diaries and the full-length novel Network Effect by Martha Wells: Action-packed roller-coaster ride with a protagonist who is easy to relate to, despite being a cynical, traumatised, paranoid part-organic/part-machine A.I.

- From a Shadow Grave by Andi C Buchanan: Several variations on a ghost story, all derived from a real 1930’s murder in Wellington.

- The Prince of Secrets and The Court of Mortals by A J Lancaster: Books 2 and 3 in the Stariel fantasy series (along with book 1, The Lord of Stariel, which I reviewed last year), continuing the saga of Henrietta Valstar, Lord of Stariel.

- The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern: Lovely, hallucinogenic, and non-linear story about two unwilling competitors trapped in a years-long contest, taking place in a magical circus.

- The Silver Path by Caitlin Spice: Fourteen fairy tales for adults, full of loss, regret, guilt, terror, obsession, and horror.

- Gideon the Ninth by Tamsin Muir: Lesbian necromancer murder mystery/space opera with swordplay.

- The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry: Historical novel set in 1895 Britain exploring the conflict between reason and faith in the context of mass hysteria over a supposed monster.

- Provenance by Ann Leckie: Science fiction set in the same universe as Leckie’s Imperial Radch/Ancillary Justice trilogy, exploring questions of identify and social cohesion.

- The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E Harrow: A portal fantasy focused on the creation and control of the portals themselves.

- The Clockill and the Thief by Gareth Ward: Further hair-raising steampunk adventures of Sin and his fellow trainee spies as they take to the skies to retrieve a stolen airship.

- Newt’s Emerald by Garth Nix: A Georgette Heyer-inspired romp with a stolen magical emerald, mistaken identity, romance, and a cross-dressing protagonist.

- Sorcerer to the Crown by Zen Cho: Another breezy Heyer-inspired Regency fantasy with a farfetched plot and a lovely romance.

- Exhalation: Stories by Ted Chiang: A collection of mind-expanding sci-fi stories using high tech to explore human nature.

- The Black God’s Drum by P. Djèlí Clark: A female-dominated steampunk-flavoured atmospheric novella set in an alternate late 19th-century New Orleans.