One January night in 1970, illustrator Simon (Si) Morley walks out of a New York City apartment and into the night of 21 January 1882. Si is a participant in a secret government project attempting time travel, but he hasn’t given much thought to what the government hopes to achieve with it; he has an agenda of his own: to solve a mystery in his girlfriend’s family history. Her grandfather shot himself, leaving a suicide note scribbled on the bottom of an old letter. The suicide note explains nothing, and contains this baffling, curiosity-provoking sentence:

That the sending of this should cause the Destruction by Fire of the entire World …[a word missing where the paper was burned] seems well-nigh incredible.

Si makes several excursions into 1882, following the few clues the grandfather had left. When he identifies the man who mailed the original letter, he rents a room in the same boarding house the man, Jake Pickering, lives in. Si soon finds himself in trouble, in both eras. In his present, the people in charge of the project lean on him to not just study the past, but to change it, and in ways he disapproves of. And in the past, there’s blackmail, accusations of murder, and Julia Charbonneau, a young woman that he quickly becomes very fond of.

Jack Finney’s classic time-travel novel, Time and Again, uses self-hypnosis as its time-travel mechanism, which is patently absurd, but then all time-travel explanations are hand-wavy magic, aren’t they? This is no more ridiculous than walking through a portal between two standing stones (the Outlander series), or a genetic abnormality that makes a person unstick from time (The Time Traveller’s Wife), or any of a dozen other equally nonsensical mechanisms. It doesn’t matter; time travel stories are fun, even without logical explanations.

The book starts off rather slowly. Si’s first excursion into the past takes place a quarter of the way in. (100 out of about 400 pages). The opening chapters describe how he is recruited to work on the project and his immersion in it. The story gets more interesting as he becomes involved in Jake and Julia’s lives, and begins to see them as real people and not just as interesting historical artefacts. The tempo quickens further in as the mystery plot takes over as the dominant story line and Si and Julia tangle with several unscrupulous men, but it never does reach the galloping pace of most modern thrillers. That wasn’t what the author was trying to accomplish, and it is a satisfying story when taken at a more leisurely pace.

Time and Again is primarily a historical novel masquerading as a mystery, with some sci-fi and romance thrown in. It was published in 1970, before cell phones and sophisticated computer graphics, so younger readers may experience it as a sort of two-pronged historical novel, traveling to both the 1880s and the late 1960s.

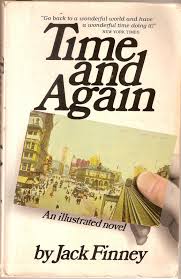

But more striking than either the mystery or sci-fi aspects is how much this book is also a love letter to New York City. Finney does a terrific job of grounding his story in a particular time and place. The book is studded with dozens of illustrations—sketches, woodcuts, and photographs, most from the 1880s—of people and places in Manhattan. Central Park, the Statue of Liberty, and the Dakota apartment building—a New York City landmark that has housed John Lennon and Yoko Ono, along with many other celebrities—play prominent parts. Despite the passage of nearly a century and a half, and the American fervour for tearing down anything slightly old and shabby and replacing it with new and shiny, surprisingly large chunks of the city are still recognisable (Or were, only a decade ago. I don’t believe it has changed that much since we moved to New Zealand in 2009.) Your enjoyment of this story will probably depend on whether the Big Apple entices or repels you. If the city appeals to you, this novel is likely to only enhance that appeal.