If I were to make a movie of All Systems Red by Martha Wells, I would open with this voiceover:

I murdered 57 humans. And then I went rogue.

Murderbot, as the part-organic android security unit (SecUnit) privately calls itself, is apathetic, cynical, introverted, and anxiety-ridden. It probably suffers from PTSD. It doesn’t remember quite what happened; the company that owns it wiped its non-organic memory. (SecUnits are expensive equipment to toss on the rubbish heap, and the company is cheap. With a new governor module installed, they assumed it would be safe to re-use.) But Murderbot’s organic neutrons still serve up distressing memories of its original governor module malfunctioning—so distressing that it hacks its new governor module to avoid ever again being in that situation.

At least, that’s what it thinks happened. It may be wrong.

Its corporate owners know how dangerous a rogue SecUnit can be. They would have no choice but to write off their investment and melt it down for scrap if they knew it was a free agent. So Murderbot carries on with its boring job, protecting its silly, stupid human clients—usually from themselves—while pretending to have a functioning governor module. It isn’t inclined to commit mass murder anyway; it would really rather numb its mind watching endless hours of downloaded entertainment serials.

Its pretence works for several years, but a few weeks into a new contract—protecting a planetary survey team that it actually respects, for a change—its clients are attacked, and Murderbot gets pissed off. As the danger mounts and the bodies pile up, Murderbot’s true nature is exposed. And when its human clients treat it like a person, the painfully shy Murderbot doesn’t know how to deal with the attention. SecUnits don’t have friends, not even other SecUnits. (Especially not other SecUnits.) Let’s just say it has trust issues: serious, justified trust issues.

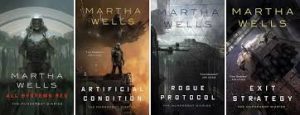

Over the course of the four novellas in the Murderbot Diaries—the Hugo and Nebulla award-winning All Systems Red, Artificial Condition, Rogue Protocol, and Exit Strategy—Murderbot goes from pretending to be a standard-issue command-driven killing machine to being a fully autonomous agent, taking responsibility and earning respect for its decisions. It learns to pass for human, too, but don’t be mistaken—it isn’t human, and doesn’t want to be. It is, however, a person, and it learns that once it starts caring, it’s hard to stop…

This action-packed space opera bounces along at a breakneck pace between pitched battles and narrow escapes, interspersed with snarky humour and touching scenes of relationship building. It also has the feel of a movie deliberately paced so fast that you’re not given time to notice how absurd it all is. With technology as advanced as artificial gravity and AI-driven spaceships, you’d think they would have computer security that wasn’t quite so vulnerable to Murderbot’s hacking. And as someone who has worked in Software Engineering for decades, that on-the-fly, dead-on-accurate hacking just wasn’t believable, nor was its ability to do the hacking while simultaneously controlling its own actions, rescuing unpredictable humans, and monitoring multiple input streams. Just how much processing power does this beast have? And how does it recharge whatever its power source is once it leaves the corporation’s repair cubicles behind?

Yeah, the old wilful suspension of disbelief got a good workout.

Despite that and a few other flaws, I enjoyed the stories immensely, because they are really more about character than plot or sci-fi tech. As with most of the best speculative fiction, the author uses a non-human to explore what it means to be human—well, maybe not human, but certainly a person—touching on issues of free will, autonomy, self-knowledge, and fear of intimacy. The protagonist is one of the more endearing and relatable constructs I can remember encountering. It constantly criticises its own actions, focusing on its mistakes and underestimating its resourcefulness, and regularly being surprised when the humans it protects react warmly towards it. Imagine: an AI suffering from imposter syndrome.

And that’s another thing I like about this series. In this imagined future, like the universe in Ancillary Justice, there’s no question about AIs having emotions. That’s simply assumed. Even the fully inorganic AI that serves as Murderbot’s unwanted mentor in Artificial Condition, the second novella, has emotions; its initial interactions with Murderbot are driven by sheer boredom. Murderbot itself is an emotional wreck at the beginning of the series. The questions about emotions here are more around how the AIs deal with them when their human owners still view them as subhuman.

A full-length novel, Network Effect, is due out soon. I’m looking forward to it.

Audience: adults and teens. Contains violence and obscenities, but no trace of sex.

Hi, Great overview / review! I too enjoyed these immensely. Thank god I’m not a software engineer (our a battery storage expert) because, as our hero says early on, his power cell is “hundreds of thousands” of hours.

Lowell

Haha, yeah, wish I had that battery tech for my electric car. Thanks for the comment!