For this year’s Banned Book Week, I re-read Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust memoir Maus. I discovered this Pulitzer-prize-winning graphic novel some thirty years ago when it was first published in book form*. It was deeply moving and disturbing then, and it hasn’t lost its punch on a re-read. It is—unfortunately!—still timely.

Maus consists of two intertwined story lines. One, set in the present day, depicts the author/artist, the child of Holocaust survivors, struggling to come to terms with his critical, demanding father and his mother’s death by suicide, and the toll that recording his father’s history takes on both of them. The other storyline, of course, is his father Vladek’s account of the war.

Vladek’s story starts in Poland in the mid-1930’s, with his courtship and marriage to the well-to-do Anja, and continues through his conscription into the Polish army. He spends some time as a German POW, then is released and reunited with Anja, but their trials are just beginning. By 1943, after being in hiding for months, they make a deal with smugglers for transportation to Hungary, but are betrayed and sent to Auschwitz, and then Dachau. That they survived seems largely due to Vladek’s resourcefulness and grit, augmented by some lucky breaks. They were helped by strong family ties and friendships, but also suffered betrayals from some they had expected to be sympathetic.

Vladek is flawed but fully human, annoying and appealing both, and all of them—Vladek, Anja, Vladek’s second wife Mala, and even Vladek and Anja’s son Art, born after the war—are deeply scarred by their experiences.

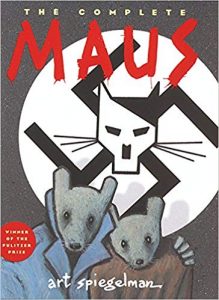

When I saw this on a list of banned and challenged comics/graphic novels, my first thought was that the challenges had come from Holocaust deniers, but that doesn’t seem to have been the case. Although there may have been some, the case study provided by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund doesn’t list any. What they do list includes objections to the visual portrayals of the different ethnic groups: Jews as mice, Germans cats, Americans dogs, and Poles pigs. That last is deeply insulting, made more so coming from a Jew, but Vladek and Anja were Poles as well as Jews, and the animosity they encountered in Poland would have been most bitter.

The other instance, where Maus was actually suppressed, serves more as a warning against over-zealous filtering. Due to the swastika on the cover, this anti-Nazi memoir was pulled from bookstore shelves in Russia in 2015 due to passage of a law forbidding Nazi propaganda. (Reminds me of the internet filters against sexually-explicit content that won’t let through useful information about the treatment of breast cancer.) In the context of history, if we avoid unpleasant topics we risk historical amnesia. As horrific as the events depicted in this book are, it is far better we be aware of them and vigilant against their reoccurrence, rather than falling back into those dark days unaware. Although lately it feels like we’re charging into the dark at full throttle with our eyes wide open.

Audience: adults, older teens.

* Individual chapters were published in Raw magazine between 1973 and 1991. The first half-dozen were collected and published as a book in 1986, the rest in a second volume in 1991. Now it’s generally packaged as a set, or in one volume. This is among the earliest to demonstrate that a graphic novel could be a powerful story-telling medium for an adult audience, not just kids’ comic books.