Lynesse Fourth Daughter, the last and therefore least important of the queen’s daughters, is her family’s wild child. The one who gives the tutors ulcers and tries her mother’s patience. She is also the only one who takes seriously the stories of a demon rampaging through the Ordwood. Who believes it is her family’s responsibility to do something about it.

Nyr Illim Tevitch, anthropologist second class, is the sole remaining member of a scientific expedition sent out as part of a far future Earth’s second, and extremely technologically advanced, wave of galactic exploration. Their mission was to study the descendants of the colonists from the first wave’s slower generation ships. When news came that things were going wrong at home, he volunteered to stay while the rest of the team travelled back to Earth in their faster-than-light ship. They were supposed to return soon. That was centuries ago, and unsurprisingly Nyr is quite depressed. He spends decades at a time in suspended animation, waking only occasionally to check his automated outpost’s maintenance logs, or when one of the locals appears on his doorstep.

Lynesse believes in magic. To fight a demon, she asks a sorcerer for help.

Nyr is a scientist. He doesn’t believe in magic, or demons. He also has a mandate not to interfere in the local’s society.

Together, they have a communication problem.

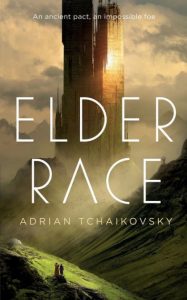

Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law—Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic—is the driving idea in Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Elder Race, one of the contenders for this year’s Hugo award in the Best Novella category. This culture clash has been done before, frequently, but it’s an idea that’s still fun when done well, because there are so many possible choices in how or even whether the magician attempts to explain the magic, and in how the other party reacts to it. Here, Nyr does attempt to explain, but Lynesse lacks the vocabulary to make sense of his explanations, a situation compounded by translation software that transforms his technical language without him realising it. The story is told in alternating chapters, her viewpoint and then his, except for one chapter where we are shown side-by-side what he says and what she hears:

Nyr: Your ancestors came to this planet from another, a place called Earth. They came in a spaceship…

Lynesse: The ancients brought men into this world from the otherworld, ferrying them upon a boat through the seas of night…

…

Nyr: And when I’ve said all that, when I’ve committed that unconscionable betrayal of all the non-contamination rules they pounded into me at anthropology HQ… Lyn says, “Yes, that is how we tell it.”

Nyr is a more fully fleshed-out character than Lynesse, with the book’s secondary focus on his struggles with depression, and his innate decency at odds with the Explorer Corp’s non-interference policy. He copes with his depression with the aid of an “Dissociative Cognition System”, which lets the higher order parts of his brain continue to reason even while aware that his body is suffering emotional stress. The drawback is that he has to regularly shut off the dissociation, and cope with his feelings, before the buildup of emotional stress overwhelms him.

There isn’t much of a plot, and the explanation of the “demon” left me scratching my head, but those are minor quibbles. From the point of view that all science fiction is about the intersection of technology and culture, and interesting only in so far as it has something to say about the human condition, this is a fine story, with a delightful blending of the fantastical and the technological.