Creeper—who doesn’t want to be called by her real name, Jacqueline—is s 13-year-old living on the streets in New Orleans. She’s an orphan, but she’s not alone; wherever she goes, Oya, the goddess of winds and storms, is with her, speaking to her, protecting her, and sometimes sending her visions. Creeper’s used to that, mostly, but the vision she’s just had of a monstrous skull, rising over the city like a lethal moon, is making her panicky. She keeps her ears open, and overhears a Haitian scientist selling a powerful weapon to the Confederacy. The weapon—the Black God’s Drums—is a sort of unilateral Mutually Assured Destruction device, capable of unleashing storms of such intensity to wipe out everyone on both sides of a conflict. Creeper takes her information to Anne-Marie St. Augustine, privateer captain of the airship, Midnight Robber, and together they set out to find the the rogue scientist before his customers can unleash wholesale destruction.

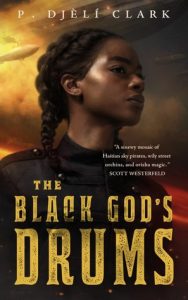

The Black God’s Drums, a fast-paced and atmospheric novella by P. Djèlí Clark, is set in a steampunk-flavoured alternate reality. In this late-19th century world, the American Civil War ground to a halt after eight years of fighting, exhaustion driving both sides to agree to an armistice. Haiti is apparently a technological powerhouse, and the free city of New Orleans exists as an independent political entity on the edge of the Confederacy. Magic abounds and African gods, among them Oya and her sister Oshun, the goddess of water, were carried across the Atlantic Ocean on the slave ships by their worshippers.

With the exception of a few Confederates and one wild girl, nearly everyone in this story is obviously or implied to be Black, without the author making a belaboured point of it. Even more remarkable for a male author, the two main characters and nearly all the named minor characters are women. The women, including the goddesses and a pair of outrageous nuns, are recognisably female without being sexualised; they simply get on with saving the world, driving the action and working together competently without fuss. How satisfying.

The climax is blatant deus ex machina, but given the prominent role the Orisha (minor gods) play throughout the story, that’s neither unexpected nor inappropriate. The narrative voice—Creeper, in first person—takes a bit of getting used to, with occasionally off-putting dialect and some word choices that are either unfamiliar (to me, anyway), invented, or alternate spellings (Maddi grá for Mardi Gras, etc.). But that’s a minor quibble.

The Black God’s Drums was a contender for the 2019 Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards. The author, an African-American historian, has written a number of other speculative fiction short works, including The Haunting of Tram Car 015, a contender for the 2020 Hugo Best Novella. (Neither won, unfortunately, but The Haunting…, set in early 20th century Egypt, is also a fun read. Check it out, too.) I’m looking forward to reading more of his writings.

Most people don’t bother reading Acknowledgements, but occasionally there is something in them worth noting. In this case, Clark does the usual thanking various people—friends, family, editors, etc.—for there help, and for introducing him to New Orleans. But then he adds,

Thanks also to the NOPD who pressed a loaded pistol to the back of my head as I lay facedown on a posh French Quarter hotel floor in a case of “mistaken identity”—you introduced me to the city, too.

And some people still refuse to believe there’s such a thing as systemic racism? Oh, please.

Trigger warning: violence, slavery, voodoo, racism (The villains’, not the author’s!), and implied sexual activity and prostitution (a couple of rather innocuous scenes inside a brothel).