With New Zealand in lockdown while the pandemic rages and our Prime Minister reminding us to be kind to one another, it seems appropriate to turn to hopepunk. What is hopepunk? I’m quoting here from a longer post by Alexandra Rowland, who defined the term:

Hopepunk says that kindness and softness doesn’t equal weakness, and that in this world of brutal cynicism and nihilism, being kind is a political act. An act of rebellion.

Hopepunk says that genuinely and sincerely caring about something, anything, requires bravery and strength. Hopepunk isn’t ever about submission or acceptance: It’s about standing up and fighting for what you believe in. It’s about standing up for other people. It’s about DEMANDING a better, kinder world, and truly believing that we can get there.

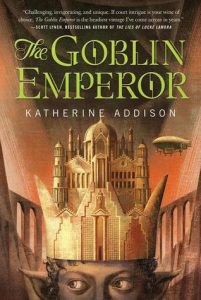

The Goblin Emperor, by American author Katherine Addison, is an exemplar of hopepunk, a story with heart. It is also one of the more enjoyable books I have read recently. Eighteen-year-old Maia is the only child of a loveless political marriage between the Emperor of the Elflands and the daughter of the neighbouring goblins’ ruler. As the emperor’s unwanted fourth son, he is never expected to figure in the succession and is raised in exile. But when an ‘accident’ kills his father and three older half-brothers, the ill-prepared Maia is as shocked as the emperor’s court to find himself on the throne. In short order he has to deal with hostile relatives, contemptuous government officials, and the rigid rules of expected behaviour for the individual at the centre of a several-thousand-year-old Byzantine society. And if that isn’t enough, the crash that killed his father and half-brothers was not an accident. Now that he is emperor, is his own life in danger?

Yes, of course his life is in danger, but the mystery simmers on the back burner for most of the book, only coming to the fore close to the end. This is a character-driven novel, not a plot-driven one. The story is rather episodic, showing Maia learning on the job to be emperor. His guiding principle throughout is to be what his cold, arrogant father was not: kind. His kindness is not mere politeness; it is the active, stubborn determination to treat everyone he comes in contact with or has authority over with respect and dignity. He offends his conservative, rigidly hierarchical housekeeper by requiring her to introduce all the household staff to him by name, confounds his secretary and personal attendants by apologising when he makes extra work for them, and upsets schedules by attending the funeral of the crew who died along with his father. And that’s just in the opening chapters.

The setting is not the bog-standard medieval fantasy world peopled with Tolkien-esque elves. There is little apparent magic and the technology level is basically steampunk. (The late emperor and his sons died in an airship crash.) The elves and goblins are almost human, with the only obviously non-human characteristic being ears that express emotion. They twitch in irritation, flatten in embarrassment, and perk up in interest. Maia’s admonition to himself at the beginning, on going to meet the messenger bringing the news, is chin and ears up.

Being almost human, the primary difference between elves and goblins is skin colour: white and black respectively. The implicit moralising about racism is pretty obvious. The two races intermix, and characters of mixed blood are accepted among the lower classes, but many of the full-blooded elvish aristocracy despise Maia for being a halfbreed.

I don’t care for stories about courtly intrigue that are heavy on betrayals and unpleasant people clawing for advantage. There is treachery here, but not by the viewpoint character. Maia is such an appealing person that I dropped all the other books I was reading (I usually have three or four going at a time) to read this one straight through. There’s not a lot of action, other than people talking, but there is plenty of conflict, and I was eager to see how Maia handled the various problems. Unfortunately, some of his successes were due more to his opponents’ stupidity rather than his or his adherents’ intelligence or devotion. Sigh. Usually that bothers me a lot, but here it’s a minor complaint.

The biggest complaint I have about The Goblin Emperor is that the author went seriously overboard in creating a vocabulary and nomenclature for her world, resulting in a word salad of characters names. Names like Pazhiro Drazharan and Varenechibal. There are dozens of named characters, and it gets confusing. The book includes a pronunciation guide and a twelve-page(!) listing of “Persons, Places, Things, and Gods.” You’ll need them. (The first printing in 2014, I believe, had them at the back of the book. My copy, from 2019, has them at the front.)

Even with the pronunciation guide, I’m not confidant I’m getting any of them right. How does one pronounce Csevet? KEVet? KeVET? Or…? And he’s one of the main characters. Reading this out loud to the rest of the family is going to be a challenge!

On the other hand, the author did a terrific job of indicating the imagined language’s distinctions in speech between first person informal (I), first person formal (we), and first person plural (we). A neat trick, given the limitations of representing that in English. After an immersion in this, you’ll be speaking in first person formal, too. Don’t believe us? Give it try; we dare you.

Audience: anyone old enough to read it. Nothing offensive.

Edit 5 April 2020: I wrote “Nothing offensive” completely forgetting a scene that could easily upset some people: the depiction of a rather gory ritual suicide. Now that I have corrected this, maybe I can erase it from my memory again…

English is remarkably deficient in words meaning we. “We” can mean the speaker (the ‘royal we’) or the speaker and the person addressed, or the speaker and some other person or people but not the person addressed, or the speaker and the person addressed but not a third specified person (or people) or…

That poor word. So overworked.

Personally, I’d love to see English reintroduce a second person singular/plural distinction (thou/you – probably more useful than using them as a second person familiar/formal distinction) but I doubt it’ll happen. Unless “y’all” or “yous” become accepted across a range of registers.

My guess for Csevet is CHEV-et, as with the actor Marton Csokas. A Hungarian name, I believe. But it’s only a guess, and having to guess does tend to jog the reader out of their book-induced trance.

I grew up in the American South. “Y’all” works for me 🙂