The time and place: early 19th century England, during the Napoleonic Wars. Miss Elinor Rochdale, on her way to take up a post of governess, alights from a stagecoach in the village of Billingshurst. She is expecting to be met—by a servant of course, not by Mrs Maccelsfield, the wealthy mother who is her new employer—so when the driver of the only other conveyance in sight asks if she is the young lady who had come down from London in answer to the advertisement, she answers that she is, and climbs into the coach. The Maccelsfield’s home is only a short distance from Billingshurst. Miles later, with the evening turning to night, she has become apprehensive. Her apprehension deepens when she is delivered to an estate in a shockingly neglected condition, and finds herself having a farcical and confusing conversation with a gentleman who knows nothing about Mrs Maccelsfield. There has been a mixup; the gentleman, Lord Carlyon (Ned), had advertised not for a governess but for a woman to marry his dissipated and disreputable cousin, Eustace Cheviot.

They are beginning to untangle the situation when Lord Carlyon’s younger brother, Nicky, bursts in with the news that Eustace is dying. The cause: he lost the fight that he provoked with Nicky—a fact that surprises no one who knows him. If Eustace is to be married, as Lord Carlyon insists on for reasons relating to an unusual inheritance, it must be immediately. The imperious aristocrat talks the confused and exhausted Elinor, against her better judgement, into marrying Eustace. (Although, to be fair, being an independent widow with a modest income isn’t a bad deal, compared to a life of drudgery as a governess.) The ceremony, performed by a clergyman also under the high-handed Carlyon’s spell, takes place in the middle of the night; by dawn Elinor is a widow.

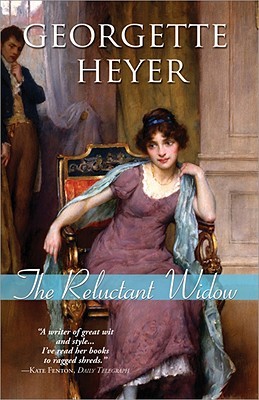

This wedding, with its dubious rationale, is all setup for the real plot in Georgette Heyer’s The Reluctant Widow. Elinor, as inheritor of Eustace’s estate, is beset. At midnight, she discovers a stranger snooping in the locked-up house. Her late husband’s relatives descend on her, and appear to be searching the house for something. Shots are fired. A murder occurs (off-screen). Elinor would rather not have anything to do with the maddeningly competent and unflappable Lord Carlyon, but she comes to rely on his good sense as what at first appeared to be a small matter grows into one with international repercussions.

I first read The Reluctant Widow years ago. It was, in fact, the first book I read by Georgette Heyer. (Heyer is considered the founder of the Regency Romance subgenre. She wrote in the mid-20th century, publishing several dozen historical novels, plus another dozen or so contemporary detective novels.) I picked the book up again recently when I needed something light and soothing to de-stress with. (The U.S. Income tax season always has me reaching for comfort reads. Not because I mind paying the tax I owe; it’s the complexity of the paperwork that drives me nuts.)

The Reluctant Widow is an old-fashioned romantic adventure. There’s no sex, and only one chaste kiss, but I’ll always prefer a slow-building romance based on good humour and compatible personalities over lust-driven insta-love stories. The romance here is actually quite subtle. (Some goodreads reviewers claim it is non-existent; YMMV.) Elinor will try to get a rise out of Ned by making an exaggerated complaint about his behaviour—usually with some valid basis—and then spoil the effect by laughing at his deadpan answer. The dialogue sparkles, and there’s a lot of humour, a good bit supplied by one charmingly volatile teenage boy (Nicky) and his independent-minded dog. Plus there’s a murderer I have difficulty labelling a villain—one of the story’s most interesting characters.

Assuming you can put up with 19th-century patronising male attitudes, the only really annoying bit was Ned’s reaction to Elinor being hit over the head; there’s a big difference between unflappable and unfeeling. And avoid the Arrow edition; it is riddled with typos.