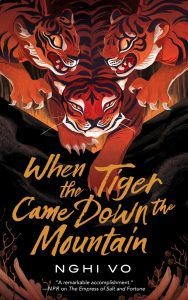

I was as captivated by When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain, the second novella in the Singing Hills Cycle by American writer Nghi Vo, as I was by the first book, The Empress of Salt and Fortune. Like that one, this book is a story within a story; in this case the framing device has a certain Scheherazade-like quality, with the cleric Chih spinning an entertaining tale to avoid being eaten.

The story opens with Chih travelling over a snowy mountain pass on the back of a mammoth, hoping to reach the shelter of a way station before dark. As they approach the way station, tigers attack out of the deepening dusk. Chih’s party reaches the shelter of a barn, and achieves a standoff: three hungry, ferocious, talking tigers on one side, and on the other, an unarmed cleric, the wounded and unconscious station keeper, the mammoth’s handler, and the mammoth. Wisely, Chih de-escalates, accepting the tigers’ claim of sovereignty over the mountains, and asking for their histories to record and take back to the abbey at Singing Hills.

The name of an illustrious tiger ancestress is mentioned; the tigers’ ears perk up. After some negotiation, the tigers settle down to hear the human’s version of the story of the shape-shifting tiger Ho Thi That and the human scholar Dieu. But, of course, the story-telling doesn’t go quite as Chih intended:

“Well,” said Sinh Loan, her voice as taut as a zither string. “Is that what they say happened?”

“It is,” said Chih. …

“How awful!” said Sinh Cam, shaking her head. “How could they, that’s the best part and they ruined it, that’s not how it went at all.”

Sinh Cam came to her feet, forcing Sinh Loan to sit up in irritation, and she packed back and forth, occasionally biting the cold air as if she wanted to get a bad taste out of her mouth.

[For context, the Sinhs are the tigers.]

The narrative shifts back and forth, Chih telling one side, the tigers telling the other, of a legend full of cultural misunderstandings, confusion, betrayal, and courtship. The mammoth handler declares that she likes the tigers’ version better, and I can see why, but both versions have their good points. The larger story, of course, is about how stories are shaped by cultural practices, and that different observers of the same events can have wildly different interpretations of them.

When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain, while equally rich and atmospheric, is a more straight-forward story than The Empress of Salt and Fortune, and with considerably lower stakes. (Although with higher stakes for Chih! But the stakes are the lives of a few individuals rather than the obliteration of an entire culture.) It is a fine successor to the first book. There will be at least two, possibly more, other books in the Singing Hills Cycle: Into the Riverlands, already published, and Mammoths at the Gate, to be published sometime this year. I am looking forward to reading more of them.