The match is entirely unsuitable. Everyone in the small British village of Edgecombe St Mary agrees on that. He, a retired career army officer, rubs shoulders with the titled and the wealthy; she’s the village shopkeeper. He’s a respected member of a family with a long history in the community; she’s the widow and daughter of Pakistani immigrants.

Except that Major Ernest Pettigrew was born in Lahore; Mrs Jasmina Ali was born in Cambridge and has never been further afield than the Isle of Wight. Brought together by sympathy for each other’s recent losses—her husband, and for him, first his wife and more recently his brother—they enjoy each other’s company, and share an appreciation for classic literature.

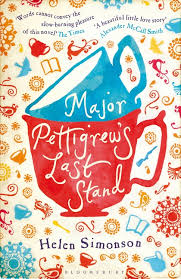

Most of the plot in Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand, by Helen Simonson, is driven by the indignities inflicted on the Major and Mrs Ali by their respective families and friends as their friendship deepens into something much more serious. The Major’s remaining family—a tactless, selfish son with bad taste and a money-grubbing sister-in-law and niece—want him to sell the family heirlooms: a matched pair of hand-crafted sporting guns given to the Major’s father by a maharaja, and then handed on, one apiece, to the Major and his now-dead brother. Mrs Ali has no children, but is under pressure from her controlling brother-in-law and his wife to turn over her shop to their son, since obviously a mere woman can’t keep it going on her own. She resents their interference, but will act against her own self-interest when her love for family demands it.

Throw in a cringe-inducing holiday gala at the Major’s golf club catered by friends of Mrs Ali, an arrogant American attempting to “develop” the village, and a fierce young single mother with a four-year-old son, and the story gets delightfully complicated. This novel is much more than a simple romance between two mature characters, although that’s appealing enough. The Major has to come to terms with his buried resentment of his father’s gift of one of the heirloom guns to his brother, and with his prejudices and blind spots towards immigrants and shopkeepers. It’s lovely to watch his senses of honour and fairness force him to grow as he is pushed out of his comfortable routine time and time again. His steps towards greater involvement with Mrs Ali’s troubled extended family are at first reluctant, but at the end he throws himself in wholeheartedly, for a bravura skirmish with a distraught youth.

Actually, the climax was rather over-the-top melodramatic, but I still enjoyed it. For me, the weakest part of the story was the character of the Major’s son, Roger, who grated on me. He was so blatantly selfish and un-self-aware that I wondered what either of the two young women he was involved with saw in him. His behaviour called into question the Major’s competence as a parent—a blot on an otherwise fine character—in making me wonder how Roger could have absorbed so little of the Major’s values.

Roger did have some merit, though, as comic relief. There is a lot of humour in this story, especially in the details about small-town life.

Audience: Anyone interested in character-driven romance. Clean, and almost violence-free.