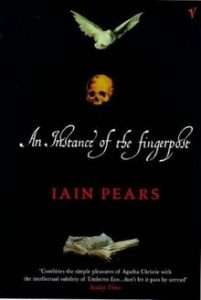

How often do you get to learn a new word just by reading the title of a book? I love historical mysteries, but I was intrigued enough to read An Instance of the Fingerpost, by Iain Pears, just to make sense of the title.

This, my friends, is a fingerpost:

This heavily-researched novel, ostensibly about a young woman’s conviction for a murder she didn’t commit, is told by four narrators, the first three of which are clearly unreliable. The 4th, claiming to be the fingerpost—the reliable guide showing the true way—does seem the most trustworthy, as he does a better job than the others of acknowledging his shortcomings, and sheds light on the plot twists and turns made increasingly murky by the 2nd and 3rd narrators. But on watching him fall into religious mysticism, and after being led so badly astray by the other three narrators, there’s room to doubt even him.

So while the true murderer is unmasked, I was left scratching my head on some other aspects of the story. This story’s plot is, if not the most complicated I’ve ever dived into, certainly one of the top five. Despite being nearly seven hundred pages long, it was dense, with little wasted or repetitious. Whenever I found myself skimming, I had to back up and re-read sections to make sure I didn’t miss some plot point. Having a scorecard would have helped. If I hadn’t discovered a list of characters, nearly all historical individuals, at the back of the book, I would have gotten quite lost.

The book has been compared to the movie Rashomon, with its conflicting points of view. I don’t know; I haven’t seen it. The movie that came to mind for me was Memento, with its under-current of delusion, and constant, disorienting reassessments.

As far as historical novels go, this is one of the most effective I’ve ever read, bringing 17th century Restoration England to life with a wealth of detail and consistency of voice. The detail is the sort to make a reader glad to be living in an era benefiting from electric lights, basic sanitation, and—in enlightened countries, anyway—publicly funded health care. This is not the kind of story that inspires romantic yearnings to return to some picturesque and unrealistic days of yore.

As gripping novels go, however, it isn’t as effective. The reviewer who said it “has you reading by torchlight under the bedclothes” didn’t match my experience. It was a bit of a slog to start with, until the first section turned into an eye-witness account of the experimentation with blood transfusions and other anatomical discoveries that began the transformation of medical practice, and then it took off. That narrator was a charming fellow; it was a shame to discover he was an out-and-out liar.

The 2nd and 3rd narrators didn’t fare as well. Both were so cruel and self-centred I didn’t enjoy the time spent with them (nearly half the book). I came close to giving up halfway through the 2nd narrator, but by then I really wanted to know how it resolved, and other reviewers said it picked up again with the 4th narrator. They were right; it did.

The 4th narrator was the most sympathetic of the four, and the one with the strongest emotional connection to the young woman at the centre of the story. The last quarter was enough (barely) to make up for the long dry section in the middle.

Earlier I said this was about a murder. That’s the plot driver, but the book is really about the nature of truth and delusion. What, if anything, that any of the four narrators have said can we believe? Are they lying outright, or are they self-deluded, and how do we ferret out the real truth, if there is one?

The reviews that call this book a tour de force are right, but it’s not to everyone’s taste. If you’re looking for light, easy escapism, forget it. But if you have a deep interest in either history, particularly English history, or the nature of truth, and don’t mind a challenge, then give it a go.

Audience: Adult only. Violence, sexual assault, gore.