The first headline to catch my eye this morning read “Pennsylvania school district reverses ban on books by authors of colour”. Excellent timing for the beginning of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Banned Book Week. Feel like celebrating? I don’t, not when the censorship involved should never have happened in the first place.

If you haven’t been following this story, here’s the short version: in October 2020 the Central York school board implemented a “freeze” on several hundred books and other educational resources while the board vetted them. The list of “frozen” titles was almost entirely by or about people of colour.

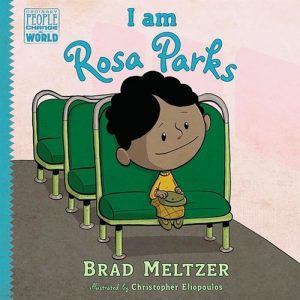

The children’s book I am Rosa Parks, in the Ordinary People Change the World series by Brad Meltzer, was on the list. I haven’t read the book; I don’t know whether whether it is accurate, age appropriate, or even well-written. I do know that Rosa Parks was a woman who looked out both for herself and for other people; a woman I can look up to, in other words. A woman lots of children, Black and White, would benefit from knowing more about.

I’ve written before about the difference between “banned” and “challenged” books. Most of the fights over books in the United States’ recent history have been challenges, not outright bans, but in this case, the materials have been prohibited from classroom use and yanked from school library shelves for over a year. This reads like a ban to me, despite the school board’s attempts to evade the term. If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, then it’s a duck.

That applies to the blatant racism involved, too. Apparently, some parents feel that books addressing issues of race and social justice are divisive. Divisive to whom? To the white snowflakes that want to close their eyes and pretend that systemic racism doesn’t exist, and that American history isn’t chock-full of political, social, and economic divisions between the races? Surely not to the people of colour who are smacked in the face every day with reminders of how much race matters and how little social justice there is for them in the U.S.

The news articles on this story quote one parent saying, “I don’t want my daughter growing up feeling guilty because she’s White.” Well, I agree, a schoolgirl isn’t responsible for the mess the United States is in; she shouldn’t feel guilty about it. But if she grows up without any understanding of the doors open to her simply because of her skin colour, and no willingness to help open those doors for others, then yes, maybe she should feel guilty. She should grow up with enough understanding of her country’s history to know that sweeping problems under the rug doesn’t build a healthy society. Her parents should encourage her to stretch her sense of empathy by reading about other people’s lives; how can that ever not be a good thing?

Fortunately, there are still many more people who do want these stories told than are against them; despite the claims of divisiveness, most of the community came together to demand the ban be lifted. I particularly like the story about a couple of women asking for donations of books on the list to put in their Little Free Libraries. The response has been more than enough to fill every Little Free Library in town; any student in the district who wants a book on the list will be able to get it.

I can understand a parent not wanting their child to grow up saddled with inappropriate guilt – but surely they don’t want them to grow up utterly ignorant either? As Hannah More said (admittedly on a different educational matter) that’s like starving to death to avoid being poisoned.

That’s a very apt analogy. Thanks!