Early in 1893, new widow Cora Seaborne escapes from London for a quieter life on the Essex shore. She isn’t grieving; her marriage was not a happy one. She is instead enjoying her new freedom to do as she pleases, tramping for miles or digging in the mud for fossils. While there, she hears stories about the Essex Serpent, a supposedly dragon-like winged creature that frightened the local peasantry in the mid-17th century. Rumours suggest that the serpent has returned and is responsible for a string of recent misfortunes: a drowning, a disappearance, etc. Cora, a firm believer in rationality and scientific advancement, is intrigued by the stories. When the natural world still throws up oddities like giant squid, who knows what might be lurking in the hidden reaches of an English estuary?

In the nearby village of Aldwinter, Reverend Will Ransome also hears the rumours, but he is not amused. Better educated than the members of his flock, he rejects the rumours as superstitious nonsense, and grows frustrated as Aldwinter’s inhabitants become increasingly uneasy.

When Cora and Will meet, sparks fly. She berates him for his faith; he questions her science that denies the grandeur of God. Despite their differences in outlook, they have much in common intellectually, and delight in arguing with each other. Cora quickly becomes close friends with Will and his wife Stella. She rents a house in Aldwinter, dividing her time between roaming the countryside and engaging in long discussions with Will under Stella’s benevolent eye.

But not all is well in this quiet corner of Essex. Cora has other devotees who don’t approve of her obsession with Will. Relationships rarely stay static—At least not in novels, or what’s the point?—and some things started in innocence and with good intentions don’t always stay that way. And there’s the serpent lurking in the shadows. As the year turns from spring to summer, a deepening sense of dread creeps over Aldwinter.

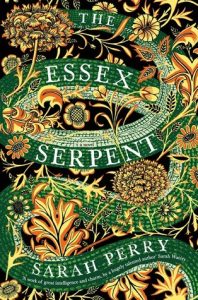

Despite the title, The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry is not about the serpent. There is something out there, hidden among the shifting sandbars and tidal mud, but it mainly serves as an ominous backdrop for the very human passions of the two main characters and their intersecting circles of family and friends. The book has touches of the gothic novel, but both the horror and drama are muted. It is much more about friendship and love, their limits and manifestations: requited and not, straight and not, acknowledged or repressed.

It is also about the tension between faith and rationality, without being a diatribe on either side. Some of the science is taken more on faith than understanding, and it’s the clergyman who is more sceptical about the existence of some sort of living fossil. There are other tangential concerns, addressed in subplots among the supporting characters, reminding us that these 19th-century people are not very different from us: societal failures in treatment of the poor, medical miracles that still leave the sufferer in wretched condition, and uneasiness towards unconventional women.

This is a beautifully-written historical novel, dense and atmospheric, with a leisurely, old-fashioned pace. It is more about the journey than the destination, and the changes to the characters involve subtle shifts rather than big, dramatic moments. It does have a few problems. Stella’s tolerance stretches credulity, and Martha, Cora’s companion/son’s nanny, is irritating. At times the subplots take over and bog things down, and the overlapping love stories felt repetitive and not all equally believable. Despite that, it’s a lovely story. It doesn’t have a conventional happy ending, but the end is still satisfying, because it is a more faithful extension of the characters we’ve come to know.